Client-Side GPU Acceleration for ZK: A Path to Everyday Ethereum Privacy

Thanks to Alex Kuzmin, Andy Guzman, Miha Stopar, Sinu, and Zoey for their generous feedback and review.

TL;DR�

- The Problem: Delegating ZK proof generation to servers often fails to preserve privacy, as the server sees your private inputs, though there are recent researches on private proof delegation 1 2 3 to mitigate this issue. Ultimately, true privacy requires client-side proving, but current performance is too slow for mainstream adoption.

- The Opportunity: Modern mobile phones and laptops contain GPUs well-suited to accelerating parallelizable ZK primitives (NTT, MSM, hashing). Benchmarks show field operations on smaller fields like M31 achieve more than 100x throughput compared to BN254 on an Apple M3 chip 4.

- The Gap: No standard cryptographic library exists for client-side GPU implementations. Projects reinvent primitives from scratch, and best practices for mobile-specific constraints (hybrid CPU-GPU coordination, thermal management) remain unexplored.

- Post-Quantum Alignment: Smaller-field operations in post-quantum (PQ) schemes (hash-based, lattice-based) map naturally to GPU 32-bit ALUs, making this exploration more valuable as the ecosystem prepares for quantum threats.

1. Privacy is Hygiene

Ethereum's public ledger ensures transparency, but it comes at a steep cost: every transaction is permanently visible, exposing users' financial histories, preferences, and behaviors. Chain analysis tools can easily link pseudonymous addresses to real-world identities, potentially turning the blockchain into a surveillance machine.

As Vitalik put it, "Privacy is not a feature, but hygiene." It is a fundamental requirement for a safe decentralized system that people are willing to adopt for everyday use.

Delegating ZK proof generation to servers undermines this hygiene. While server-side proving is fast and convenient, it requires sharing raw inputs with third parties. Imagine handing your bank statement to a stranger to "anonymize" it for you. If a server sees your IP or, even worse, your transaction details, privacy is compromised regardless of the proof's validity. Though recent studies explore private delegation of provers 1, true sovereignty requires client-side proving: users generate proofs on their own devices, keeping data private from the start.

This is especially critical for everyday Ethereum privacy. Think of sending payments, voting in DAOs, or managing identity-related credentials (e.g. health records) without fear of exposure. Without client-side capabilities, privacy-preserving tech remains niche, adopted only by privacy-maximalist geeks. Hence, accelerating proofs on consumer hardware could be the bedrock for creating mass adoption of privacy, making it as seamless as signing a transaction today.

2. GPU Acceleration: A Multi-Phase Necessity for Client Proving

Committing resources to client-side GPU acceleration for ZKP is both a short-term and long-term opportunity for Ethereum's privacy landscape. GPUs excel at parallel computations, aligning perfectly with core primitives that could be used in privacy-preserving techs like ZKP and FHE, and client devices (phones, laptops) increasingly feature growing GPU capabilities. This could reduce proving times to interactive levels, fostering mass adoption.

Current Status and Progress

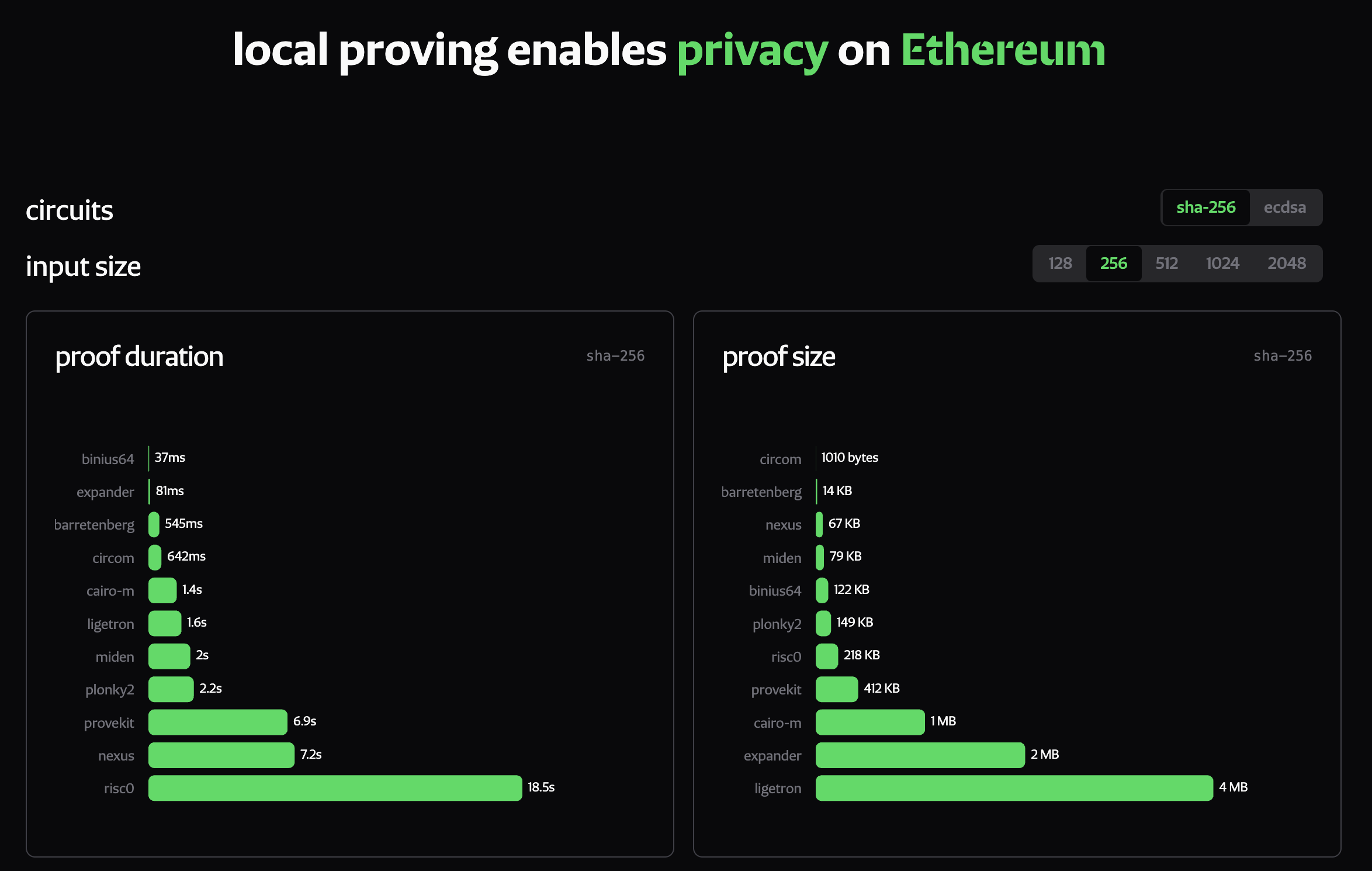

Although client-side proving is a reality, the user experience is still catching up. CSP benchmarks from ethproofs.org show that while consumer devices can now generate proofs in seconds, the process often takes longer than 100ms. For scenarios requiring real-time experience, like payments or some DeFi applications, this delay creates noticeable friction that hinders adoption.

|

|---|

| CSP benchmarks from ethproofs.org 5. Snapshot taken on January 19, 2026 |

Several zkVM projects working on real-time proving have leveraged server-side GPUs (e.g. CUDA on RTX-5090) for ~79x improvement on average proving times, according to site metrics from Jan 28, 2025 to Jan 23, 2026, validating the potential of GPU acceleration for proving.

On the client side, though still in the early stages of PoC and exploration, several projects highlight potential:

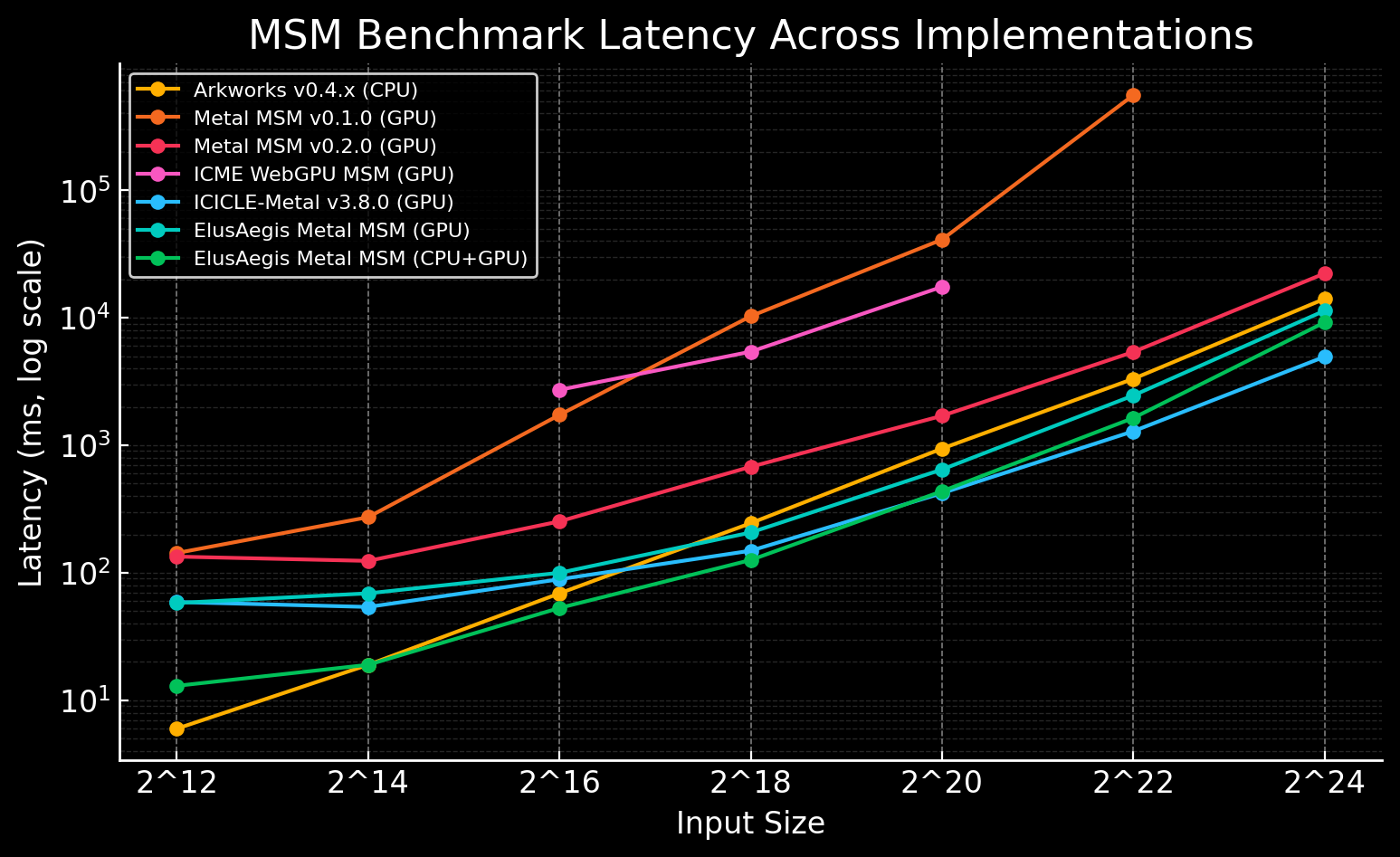

- Ingonyama ICICLE Metal: Optimizes ZK primitives such as MSM and NTT for Apple's Metal API, achieving up to 5x acceleration on iOS/macOS GPUs (v3.6 release detailed in their blog post).

- zkMopro Metal MSM v2: Explores MSM acceleration on Apple GPUs, improved 40-100x over v1. For details, check this write-up. Building on ZPrize 2023 winners Tal and Koh's WebGPU innovations (inspired by their implementation) 6.

- Ligetron: Leverages WebGPU for faster SHA-256 and NTT operations, enabling cross-platform ZK both natively and in browsers.

Broader efforts from ZPrize and Geometry.xyz underscore growing momentum, though protocol integration remains limited 78.

Opportunities for Acceleration

Several ZK primitives are inherently parallelizable, making GPUs a natural fit:

- MSM (Multi-Scalar Multiplication): Sums scalar multiplications on elliptic curves; parallel via independent additions, bottleneck in elliptic curve-related schemes.

- NTT (Number Theoretic Transform): A fast algorithm for polynomial multiplication similar to FFT but over finite fields; parallel via butterfly ops, core to polynomial operations in many schemes.

- Polynomial Evaluation and Matrix-Vector Multiplication: Computes polynomial values at points or matrix-vector products; high-throughput on GPU shaders via SIMD parallelism.

- Merkle Tree Commitments: Builds hashed tree structures for efficient verification; parallel-friendly for batch processing and hashing.

Additionally, building blocks in interactive oracle proofs (IOPs), such as the sumcheck protocol 9, which reduces multivariate polynomial sums to univariate checks, benefit from massive parallelism in tasks such as summing large datasets or verifying constraints. While promising for GPU acceleration in schemes like WHIR 10 or GKR-based systems 11, sumcheck is not currently the primary bottleneck in most polynomial commitment schemes (PCS).

These primitives map directly to bottlenecks in popular PCS, as shown in the table below.

| PCS Type | Typical Schemes | Family (Hardness Assumption) | Primary Prover Bottleneck | Acceleration Potential | PQ Secure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KZG 12 | Groth16, PlonK, Libra | Pairing-based (-SDH) | MSM | Moderate: Memory-bandwidth limited | No |

| IPA 13 | Halo2, Bulletproofs, Hyrax | Discrete Log (DL) | MSM | Moderate: Parallel EC additions | No |

| Hyrax 14 | GKR-based SNARKs | Discrete Log (DL) | MSM | Moderate: Similar to IPA but multilinear | No |

| LaBRADOR 15 | LaBRADOR-based SNARKs | Lattice-based (SIS / LWE) | NTT, Matrix-Vector Ops | High: Fast small-integer arithmetic | Yes |

| FRI 16 / STIR 17 | STARKs, Plonky2 | Hash-based (CRHF) | Hashing, NTT | High: Extremely parallel throughput | Yes |

| WHIR 10 | Multivariate SNARKs | Hash-based (CRHF) | Hashing | High: Extremely parallel throughput | Yes |

| Basefold 18 | Basefold-SNARKs | Hash-based (CRHF) | Linear Encoding & Hashing | High: Field-agnostic parallel encoding | Yes |

| Brakedown 19 | Binius, Orion | Hash-based (CRHF) | Linear Encoding | High: Bit-slicing (SIMD) | Yes |

Table 1: ZK primitives mapped to PCS bottlenecks and GPU potential

Moreover, VOLE-based ZK proving systems, such as QuickSilver 20, Wolverine 21, and Mac'n'Cheese 22, utilize vector oblivious linear evaluation (VOLE) to construct efficient homomorphic commitments. These act as PCS based on symmetric cryptography or learning parity with noise (LPN) assumptions. The systems are post-quantum secure. Their main prover bottlenecks are VOLE extensions, hashing, and linear operations, which make them well-suited for GPU acceleration through parallel correlation generation and batch processing.

In the short term, primitives related to ECC (e.g. MSM in pairing-based schemes) are suitable for accelerating existing, well-adopted proving systems like Groth16 or those using KZG commitments, providing immediate performance gains for current Ethereum applications.

Quantum preparedness adds urgency for the long term: schemes on smaller fields (e.g. 31-bit fields like Mersenne 31, Baby Bear, or Koala Bear 23) align better with GPU native words (32-bit), yielding higher throughput. Field-Ops Benchmarks 4 confirm this. Under the same settings (not optimal for max performance but for fairness of experiment), smaller fields like M31 achieve over 100 Gops/s on client GPUs, compared to <1 Gops/s for larger ones like BN254.

| Operation | Metal GOP/s | WebGPU GOP/s | Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| u32_add | 264.2 | 250.1 | 1.06x |

| u64_add | 177.5 | 141.1 | 1.26x |

| m31_field_add | 146.0 | 121.7 | 1.20x |

| m31_field_mul | 112.0 | 57.9 | 1.93x |

| bn254_field_add | 7.9 | 1.0 | 7.64x |

| bn254_field_mul | 0.63 | 0.08 | 7.59x |

As quantum tech advances, exploration related to PQ primitives (e.g. lattice-based or hash-based operations) will drive mid-to-long-term client-side proving advancements, ensuring resilience against quantum threats like "Harvest Now, Decrypt Later" (HNDL) attacks, as mentioned in the Federal Reserve HNDL Paper and underscored by the Ethereum Foundation's long-term quantum strategy, which is a critical factor if we are going to defend people's privacy on a daily-life scale.

3. Challenges: Bridging the Gap to Everyday Privacy

Despite progress, some hurdles remain between the current status and everyday usability.

3.1 Fragmented Implementation

- No standard crypto library exists for client-side GPUs, forcing developers to reinvent wheels from scratch, which is often not fully optimized.

- Lack of State-of-the-Art (SoTA) references for new explorations, leading to duplicated efforts.

- Inconsistent benchmarking: metrics like performance, I/O overhead, peak memory, and thermal/power traces are rarely standardized, complicating comparisons. Luckily, PSE's client-side proving team is improving this 5.

3.2 Limited Quantum-Resistant Support

Most GPU accelerations have focused on PCS related to elliptic-curve cryptography (ECC) like IPA, Hyrax, and KZG (pairing-based). All are vulnerable to quantum attacks via Shor's algorithm. These operate on larger fields (e.g. 254-bit), inefficient for GPUs' 32-bit native operations, and schemes like Groth16 face theoretical acceleration upper bounds, as analyzed in Ingonyama's blog post on hardware acceleration for ZKP 24. On the other hand, PQ schemes such as those based on lattices or hashes (e.g. FRI variants) are underexplored on client GPUs but offer greater parallelism.

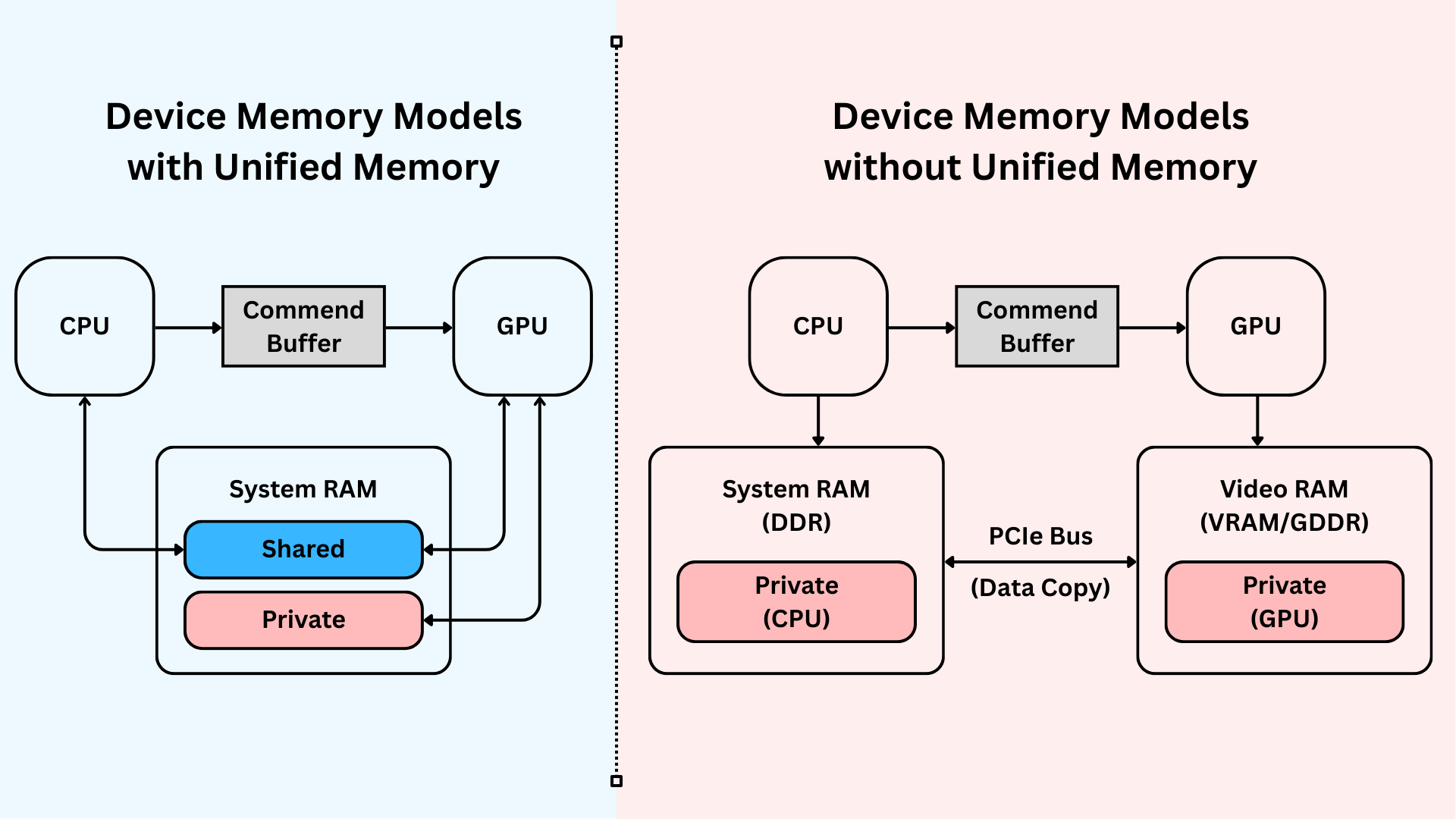

3.3 Device-Specific Constraints

Client devices differ vastly from servers: limited resources, shared GPU duties (e.g. graphics rendering), and thermal risks. Blindly offloading to GPUs can cause crashes or battery drain 25 26. Hybrid CPU-GPU approaches, inspired by Vitalik's Glue and Coprocessor architecture, need further exploration. Key unknowns include:

- Task dispatching hyperparameters.

- Caching in unified memory. Check Ingonyama's Metal PoC for zero-cost CPU-GPU transfers.

- Balancing operations: GPUs for parallelism, CPUs for sequential tasks.

|

|---|

| Apple GPUs have the unified memory model in which the CPU and the GPU share system memory |

4. PSE's Roadmap for GPU Acceleration

To achieve client-side GPU acceleration's full potential, we propose a structured roadmap focused on collaboration and sustainability:

-

Build Standard Cryptography GPU Libraries for ZK

- Mirror Arkworks's success in Rust zkSNARKs: Create modular, reusable libs optimized for client GPUs (e.g. low RAM, sustained performance) 27.

- Prioritize PQ foundations to enable HNDL-resistant solutions. For example, lattice-based primitives like NTT that scale with GPU parallelism 28.

- Make it community-owned, involving Ethereum, ZK, and privacy ecosystems for joint development, accelerating iteration and adoption in projects like mobile digital wallets.

-

Develop Best-Practice References

- Integrate GPU acceleration into client-side suitable protocols, including at least one PQ scheme and mainstream ones like Plonky3 29 or Jolt 30.

- Optimize for mobile, tuning for sustained performance over peaks and avoiding thermal throttling via hybrid CPU-GPU coordination.

- Create demo protocols as end-to-end references running on real devices with GPU boosts, serving as "how-to" guides for adopting standard libs.

This path transitions from siloed projects to ecosystem-wide tools, paving the way for explorations in sections like our starting points below.

5. Starting Points

zkSecurity's WebGPU overview highlights its constraints versus native APIs like Metal or Vulkan. For example, limited integer support and abstraction overheads.

To validate, a PoC was conducted to compare field operations (M31 vs. BN254) across APIs 4. Key findings:

- u64 Emulation Overhead: Metal's native 64-bit support edges WebGPU (1.26x slower due to u32 emulation), compounding on complex ops.

- Field Size vs. Throughput: Smaller fields shine. M31 hits 100+ Gops/s; BN254 <1 Gops/s (favoring PQ schemes).

- Complexity Amplifies Gaps: Simple u32 ops show parity (1.06x); advanced arithmetic like Montgomery multiplication widens to 7x for BN254.

Start with native APIs first, such as Metal for iOS (sustainable boosts), then WebGPU for cross-platform reach. This prioritizes real-world viability over premature optimization.

6. Conclusion

Client-side GPU acceleration for ZKPs represents both immediate and long-term opportunities for Ethereum privacy, potentially improving UX for adopting privacy-preserving tech and enabling quantum-secure daily-life use cases like private payments. By addressing fragmentation, embracing PQ schemes, and optimizing for mobile devices, we can make privacy "hygiene" for everyone (from casual users to privacy-maximalists). We believe that with collaborative efforts from existing players and the broader community, everyday Ethereum privacy is within reach.

Footnotes

-

Kasra Abbaszadeh, Hossein Hafezi, Jonathan Katz, & Sarah Meiklejohn. (2025). Single-Server Private Outsourcing of zk-SNARKs. Cryptology ePrint Archive. https://eprint.iacr.org/2025/2113 ↩ ↩2

-

Takamichi Tsutsumi. (2025). TEE based private proof delegation. https://pse.dev/blog/tee-based-ppd ↩

-

Takamichi Tsutsumi. (2025). Constant-Depth NTT for FHE-Based Private Proof Delegation. https://pse.dev/blog/const-depth-ntt-for-fhe-based-ppd ↩

-

Field-Ops Benchmarks. GitHub. https://github.com/moven0831/field-ops-benchmarks ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Proving Backends Benchmarks by Client-side Proving Team from PSE. https://ethproofs.org/csp-benchmarks ↩ ↩2

-

ZPrize 2023 Entry: Tal and Koh's WebGPU MSM Implementation. GitHub. https://github.com/z-prize/2023-entries/tree/main/prize-2-msm-wasm/webgpu-only/tal-derei-koh-wei-jie ↩

-

ZPrize. (2023). Announcing the 2023 ZPrize Winners. https://www.zprize.io/blog/announcing-the-2023-zprize-winners ↩

-

Geometry: Curve Arithmetic Implementation in Metal. GitHub. https://github.com/geometryxyz/msl-secp256k1 ↩

-

Carsten Lund, Lance Fortnow, Howard Karloff, & Noam Nisan. (1992). Algebraic methods for interactive proof systems. Journal of the ACM (JACM). https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/146585.146605 ↩

-

Gal Arnon, Alessandro Chiesa, Giacomo Fenzi, & Eylon Yogev. (2024). WHIR: Reed–Solomon Proximity Testing with Super-Fast Verification. Cryptology ePrint Archive. https://eprint.iacr.org/2024/1586 ↩ ↩2

-

Shafi Goldwasser, Yael Tauman Kalai, & Guy N. Rothblum. (2008). Delegating computation: interactive proofs for muggles. In Proceedings of the fortieth annual ACM symposium on Theory of computing. https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/1374376.1374396 ↩

-

Aniket Kate, Gregory M. Zaverucha, & Ian Goldberg. (2010). Constant-Size Commitments to Polynomials and Their Applications. In Advances in Cryptology - ASIACRYPT 2010. Springer. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-642-17373-8_11 ↩

-

Jonathan Bootle, Andrea Cerulli, Pyrros Chaidos, Jens Groth, & Christophe Petit. (2016). Efficient Zero-Knowledge Arguments for Arithmetic Circuits in the Discrete Log Setting. Cryptology ePrint Archive. https://eprint.iacr.org/2016/263 ↩

-

Riad S. Wahby, Ioanna Tzialla, abhi shelat, Justin Thaler, & Michael Walfish. (2017). Doubly-efficient zkSNARKs without trusted setup. Cryptology ePrint Archive. https://eprint.iacr.org/2017/1132 ↩

-

Ward Beullens & Gregor Seiler. (2022). LaBRADOR: Compact Proofs for R1CS from Module-SIS. Cryptology ePrint Archive. https://eprint.iacr.org/2022/1341 ↩

-

Eli Ben-Sasson, Iddo Bentov, Yinon Horesh, & Michael Riabzev. (2018). Scalable, transparent, and post-quantum secure computational integrity. Cryptology ePrint Archive. https://eprint.iacr.org/2018/046 ↩

-

Gal Arnon, Alessandro Chiesa, Giacomo Fenzi, & Eylon Yogev. (2024). STIR: Reed–Solomon Proximity Testing with Fewer Queries. Cryptology ePrint Archive. https://eprint.iacr.org/2024/390 ↩

-

Hadas Zeilberger, Binyi Chen, & Ben Fisch. (2023). BaseFold: Efficient Field-Agnostic Polynomial Commitment Schemes from Foldable Codes. Cryptology ePrint Archive. https://eprint.iacr.org/2023/1705 ↩

-

Alexander Golovnev, Jonathan Lee, Srinath Setty, Justin Thaler, & Riad S. Wahby. (2021). Brakedown: Linear-time and field-agnostic SNARKs for R1CS. Cryptology ePrint Archive. https://eprint.iacr.org/2021/1043 ↩

-

Kang Yang, Pratik Sarkar, Chenkai Weng, & Xiao Wang. (2021). QuickSilver: Efficient and Affordable Zero-Knowledge Proofs for Circuits and Polynomials over Any Field. Cryptology ePrint Archive. https://eprint.iacr.org/2021/076 ↩

-

Chenkai Weng, Kang Yang, Jonathan Katz, & Xiao Wang. (2020). Wolverine: Fast, Scalable, and Communication-Efficient Zero-Knowledge Proofs for Boolean and Arithmetic Circuits. Cryptology ePrint Archive. https://eprint.iacr.org/2020/925 ↩

-

Carsten Baum, Alex J. Malozemoff, Marc B. Rosen, & Peter Scholl. (2020). Mac'n'Cheese: Zero-Knowledge Proofs for Boolean and Arithmetic Circuits with Nested Disjunctions. Cryptology ePrint Archive. https://eprint.iacr.org/2020/1410 ↩

-

Voidkai. Efficient Prime Fields for Zero-knowledge proof. HackMD. https://hackmd.io/@Voidkai/BkNX3xUZA ↩

-

Ingonyama. (2023, September 27). Revisiting Paradigm’s “Hardware Acceleration for Zero Knowledge Proofs”. Medium. https://medium.com/@ingonyama/revisiting-paradigms-hardware-acceleration-for-zero-knowledge-proofs-5dffacdc24b4 ↩

-

"GPU in Your Pockets", zkID Days Talk at Devconnect 2025. https://streameth.org/6918e24caaaed07b949bbdd1/playlists/69446a85e505fdb0fa31a760 ↩

-

Benoit-Cattin, T., Velasco-Montero, D., & Fernández-Berni, J. (2020). Impact of Thermal Throttling on Long-Term Visual Inference in a CPU-Based Edge Device. Electronics, 9(12), 2106. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics9122106 ↩

-

Arkworks. https://arkworks.rs/ ↩

-

Jillian Mascelli & Megan Rodden. (2025, September). “Harvest Now Decrypt Later”: Examining Post-Quantum Cryptography and the Data Privacy Risks for Distributed Ledger Networks. Federal Reserve Board. https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/feds/files/2025093pap.pdf ↩

-

Plonky3. GitHub. https://github.com/Plonky3/Plonky3 ↩

-

Jolt. GitHub. https://github.com/a16z/jolt ↩